Groupe Thales

Dominique Vernay, Technical Director of the Thales group is also a member of Onera's Board of Directors and President of the System@tic competitive cluster. Here he talks about the benefits a partnership with Onera brings to an industrial company.

"

Signature of the Onera - Thales Air Systems agreement (June 2006). Seated, Denis Maugars, President of Onera, and Thierry Beauvais, Research & Technology Vice-President of Thales Air Systems. Standing, on the right, Dominique Vernay.

Interview

What is Onera's position generally speaking in its partnerships with Thales?

Dominique Vernay: Our group bases its technological excellence on a long tradition of partnerships which leads us to adopt an open model of innovation. We have found that success is founded on the variety of technologies implemented. This implies a multitude of partners. For the basic technologies, like electronics, there are numerous and varied partners. Conversely, for the application aspects, our collaborations are more restricted and we always employ a small number of players. Onera is one of them, an indispensable one with which we try out a good number of our final systems in the fields of radar detection and optronics and which lead directly to some of our products. That's as good as saying that Onera occupies a strategic position in the value added chain in terms of positioning and knowledge

Have you got some examples of applications in mind?

DV: The very fine grain knowledge of wave propagation phenomena is a cornerstone of the systems that we make in the fields of radar and optronics. It conditions their performance and quality, the source of their competitiveness. Onera's knowledge of radar is unique in France and rare in Europe. It increases our systems' detection capabilities and resistance to jamming and makes Onera the preferred partner of Thales for both ground radars and airborne systems. The other field of excellence that we have in common is optronics. Onera has facilities for testing and characterizing targets that are unique in their quality, which is essential for optimizing systems. This means that the Thales and Onera teams often work together to meet the requirements set by the French Armaments Procurement Agency.

Don't these activities generate any competition?

DV: Yes, there is competitiveness between our teams and those of Onera, but at a low level. It encourages our respective creativity in a confrontation of ideas and points of view. This "competitive collaboration" has been the basis for the success of our partnership, like, for example in the field of passive radars. That said, there are also fields in which Onera has knowledge that Thales lacks, in particular that of low frequency radars.

Are these successes leading to any other collaborations?

DV: Yes, firstly, they are encouraging us to continue with the work, for example, on passive radars which have not yet yielded their full potential for innovation. Onera’s expertise remains essential for our development, just as it was for low frequency radars. It enables us to plan new directions for work, particularly in airborne turbulence detection systems, a crucial problem for air transport because it conditions the minimum distance between two aircraft. We now know how to detect these phenomena using radars or lidars and we know about the problems of airborne avionics. Onera provides us with its wide knowledge of atmospheric phenomena. The collaboration has started and its quality gives cause for hope of some innovations in the coming years.

How do you see this collaboration developing?

DV: In the case of drones, one of the major problems is their insertion into air traffic. One condition of their success is that they must not create an additional risk, in either the military or civil field. Two divisions of Thales are working on it jointly, the Aeronautics division (airborne systems) and the Aerial Systems division (air traffic management), in collaboration with the Onera teams. Elsewhere, environmental concerns, which are becoming increasingly pressing, are leading us to re-examine some fundamental aspects of systems. In both cases, we are counting on Onera's skills.

To summarize, what do you gain from the partnership with Onera?

DV: Aeronautics and the management of air space are fields in which many players are involved and for which we are developing sub-assemblies of complex systems. Therefore, it is not surprising if the leading position occupied by Thales is the result of a strategy of judiciously chosen partnerships. The success of these activities is first of all the result of our ability to access the "right" knowledge. On this point, our partnership with Onera has proved its worth. We also have to be able to optimize our systems, and here, once again, Onera provides us with its skills, equipment and knowledge. This is why the collaboration between Thales and Onera is strong throughout the life of our projects, typically in the region of ten years, both in the phases of research and development.

Supplement to the interview with Dominique Vernay

Passive radars

See without being seen

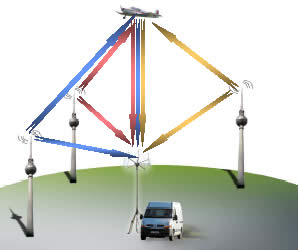

Powerful, but regular and locatable, radar surveillance installations can be by-passed by stealth aircraft: geometry calculated to reflect the waves in different directions from that of the radar, slow flight at low altitude. Stealth targets thread their way through the meshes of a net that they know well. These meshes can however close up and become invisible themselves! This is passive radar.

The principle

Passive radars use "third-party transmitters", such as the antennae that transmit television or FM band radio signals over the air waves. Just like those from traditional radars, these waves are reflected by the target and their echo can be found amongst these signals.

The advantages

- The frequency of the signals used is lower than that of traditional radars: FM radio (88-108 MHz) and television (400 to 800 MHz). Now, the lower the frequency the larger the surface that the target seems to have. Therefore, the system is suitable for detecting small flying objects.

- The lower frequency of the signals and their limited range in relation to traditional radar orients these systems towards the detection of slow moving and low flying targets, which may be characteristic of stealth intrusions.

- The absence of active transmission gives the system a stealth character that is suited to the surveillance of frontier areas.

- There are no electromagnetic compatibility problems.

- Finally, the limits imposed by the regulations on the ranges of the electromagnetic spectrum allocated to radar applications favor the use of this method.

The difficulties

- The multiple reflections and compensations that make signal processing more complex.

- The computing power necessary. Although the principle of passive radar has been known since the 1920s, extracting the signal has remained an insurmountable problem before the recent increase in computing power. With 100 GFlops, or one hundred billion floating point operations per second – the computing power that has become available in the last three or four years - signal processing in real time has become a possibility.

- The change in TV and radio signals from analog to digital modifies the computational analysis but opens up new possibilities.

Industrial development

There are not yet many industrial players in this emerging field. But the situation may change quickly.

Atmospheric turbulence is an issue for air transport comfort and safety. This phenomenon may have several causes: the closeness of clouds, variations in local temperatures, orographic waves… pilots know these areas well and avoid them for the well-being of their passengers. But, can turbulence be detected when it occurs in front of the aircraft in flight and in clear air?

Yes, using a lidar.

The principle

A lidar is a laser coupled with a sensor. It analyses the laser light reflected by the molecules encountered. It measures either the variation in the density of the air or the speed of the molecules by the Doppler effect. In this way, sudden variations in the wind field in front of the aircraft are detected.

The advantages

- Direct detection of turbulence in clear air, i.e. without the presence of drops or aerosols (traditional meteorological radar has a long range but only sees clouds).

- The setting up of a surveillance network on a planetary scale using airborne lidars and communications between users. In the long term, the generalized use of atmospheric lidar will improve knowledge of the environment, as was the case with the TAWS surveillance system (Collision with the ground, traffic and meteorological surveillance).

The difficulties

Airborne lidar must have a long enough detection range to enable the aircraft to avoid the areas of turbulence. But the current weight and size of such long range devices are still totally impractical.

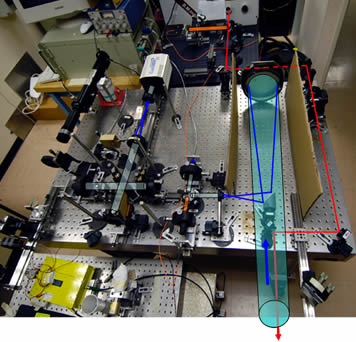

Onera research bench (Theoretical and Applied Optics Department) with a Rayleigh lidar for measuring air parameters

The research efforts

They are part and parcel of our response to the needs of airlines.

- In the long term, aircraft should be able to detect turbulences up to 50 Km in front of the aircraft and therefore be able to avoid it.

- In the medium term, a range of 10 to 20 Km in front of the aircraft should be achievable. This is the equivalent of two to three minutes flight and leaves enough time to prepare the cabin in order to minimize discomfort and the risk of injury to passengers.

- In the short term, it will be possible to detect turbulence just in front of the aircraft and manage the flight controls as a consequence: the aircraft will be able to "make the best of it" automatically.

Industrial development

A European consortium has associated a number of partners (Thales, Onera, DLR, CNRS, etc.) for developing this lidar. The preliminary work started four years ago. Onera is a partner of Thales for the system modeling aspects and a partner of CNRS for atmospheric turbulence data acquisition and modeling. Onera's expertise in lidar design and end-to-end modelling are key factors for industrial success.

The next steps

The principle of detection must be validated in different configurations and an airborne demonstrator built.